The Languages of Timor-Leste

Hi again everyone,

In addition to my regular monthly(ish) updates from Timor-Leste, I would like to begin a new series of posts dedicated to linguistics in Timor-Leste. Living here, I encounter new things everyday related to language that I find fascinating as a linguist. I realize that not everyone who is interested in updates about my life as a Peace Corps volunteer will be interested in reading this new series — and thats ok! Much of this is to indulge my own curiosity, and if you are interested in following along, that’s great! If not, no worries at all.

Before being reassigned from Peace Corps Vanuatu to Peace Corps Timor-Leste, I made my first post on this Substack: The Languages of Vanuatu. Long story short, Vanuatu has the highest linguistic diversity of any country in the world by the metrics of both population and area with an estimated 138 languages spoken by its population. This was a big reason behind my excitement for my service. By comparison, the ~20 languages (Ethnologue 2023) spoken in Timor-Leste may seem paltry but as you’ll read here, East Timor’s linguistic landscape is a fascinating mosaic that highlights the country’s pre- and post-colonial history. This post will be the first in a new series about linguistics in Timor-Leste and will provide you a general overview of the languages of East Timor. It’ll also serve as context and background for future additions.

Here’s a TL;DR of how this all relates to my experience as a Peace Corps volunteer for those who’d rather not get into all the details below:

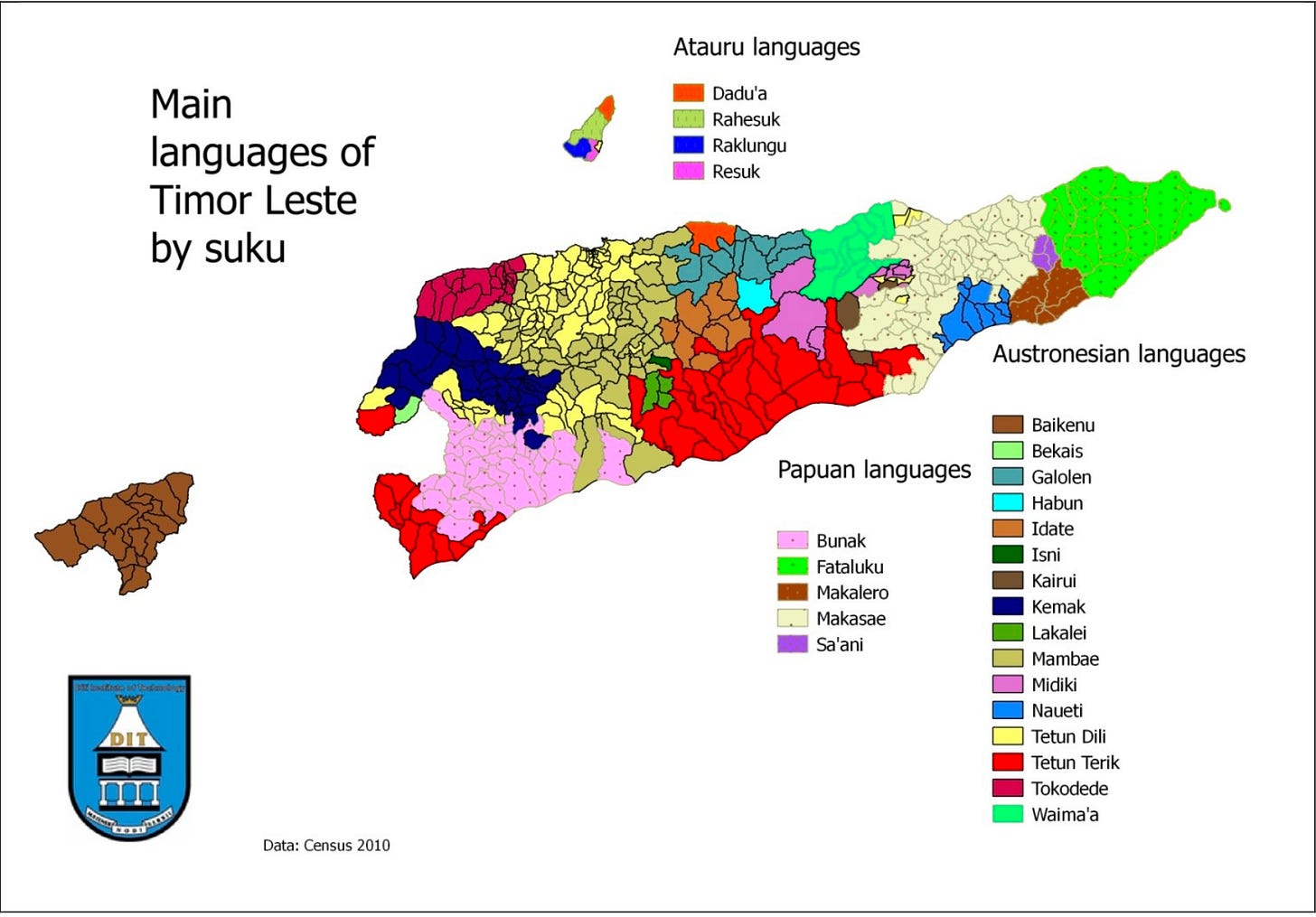

Here in Venilale Administrative Post, three languages are spoken in addition to the lingua franca Tetun: Waima’a, Midiki, and Makasae. The area or suco (village) within Venilale where someone is from generally indicates which language they speak. For exmaple, my suco Fatulia is almost completely Midiki, my friend Quentin’s in Bercoli is Waima’a, and a nearby suco called Uai Oly is Makasae. It’s fascinating to see such dense linguistic diversity around me everyday; I can walk 20 minutes and be in a different language community; And going to the market, I hear a mixture of Tetun, Waima’a, Midiki, and Makasae all being spoken around me.

Waima’a and Midiki are closely related and, for the most part, mutually intelligible, but Makasae is in a completely different language family as you’ll find out below. This close proximity has certainly led to reciprocal linguistic influences on the languages’ lexicons, grammars, and phonologies. Although Midiki and Waima’a are Austronesian languages, a sizable amount of their lexicon is Papuan in origin as a result of language contact. Similarly, Makasae features many words of Austronesian origin from extended contact with the eastern-most Austronesian languages in Timor: Waima’a, Midiki, and Naueti.

Makasae: gehere ‘to think’ | Waima’a/Midiki: gere ‘to think’

Makasae: ana ‘person’ | Waima’a/Midiki: ana ‘child’

Overview

As you can see from the map above, the languages spoken in East Timor can be categorized within two overarching language families: Austronesian (distantly related to languages like Tagalog, Malay, Hawaiian, etc.) and Papuan (non-Austronesian languages)1.

At a government level, Timor-Leste has two official languages — Tetun and Portuguese — a reflection of the country’s history. For four centuries, Timor-Leste was a colony of the Portuguese, who primarily came to the island to profit from Timor’s sandalwood. As time progressed, Catholic missionaries also began to arrive in Portuguese Timor in an effort to convert the local population. Even in this time, Tetun served as a lingua franca, allowing disparate linguistic groups to communicate with each other and with the Portuguese colonizers.

After winning independence from 24 years of brutal Indonesian occupation, the new Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (Port. República Democrática de Timor-Leste) declared Tetun and Portuguese as co-official languages. Portuguese’s status as an official language raises some interesting questions and challenges, which I will get into in a future post.

The Austronesian Languages of Timor-Leste

Austronesian languages, just like in other parts of Maritime Southeast Asia and the Pacific, make up the vast majority of the languages spoken in Timor-Leste. Below I will outline a few (but certainly not all) of the Austronesian languages of East Timor:

[Note: All speaker numbers used in this post are taken from Ethnologue (2023), which are based on the results of the 2015 Timor-Leste Census. The detailed results of the most recent 2022 Census have yet to be released]

Tetun Dili (aka Tetun Prasa): ~944,000 speakers around Timor-Leste (Ethnologue 2

One of Timor-Leste’s two official languages, the lingua franca across the country, and the language I speak the majority of the time at home, work, and around the community.

Tetun Dili has been influenced to some degree by Portuguese, and to a lesser extent Bahasa Indonesia and Mambai. The Portuguese influence is most notably lexically, as many of the words used everyday are borrowed from Portuguese (especially in the acrolect). Despite this influence and previous discourse, it is generally agreed that Tetun Dili is not a creole but rather an Austronesian language with numerous Portuguese loan words (Chen 2015).

Tetun Terik: ~91,200 speakers along the southern coast of Timor-Leste

Tetun Dili’s more linguistically conservative sister, Tetun Terik is spoken in two distinct areas of the country along the coast of the Timor Sea. Tetun Dili speakers have told me they can understand Tetun Terik when it is spoken, but cannot produce it themselves.

Mambai (also spelled Mambae): ~273,000 speakers in much of the mountainous regions of western Timor-Leste

This is actually a syllabic abbreviation of four languages or varieties (some may term these ‘lects’). These four languages are closely related and are the eastern-most Austronesian languages spoken in Timor. Due to insufficient documentation, it is difficult to determine whether each of the four are distinct languages or varieties/dialects of one ‘Kaiwaimina’ language.

Waimoa (aka Waima’a): ~26,870 speakers in Vemasse, Baucau, and Venilale Adminstrative Posts

Midiki: ~17,420 speakers in Venilale Administrative Post and parts of Viqueque Municipality

This is the language spoken by much of my community here in Venilale. It’s been very fun to learn to speak Midiki with my family, neighbors, and fellow teachers at school, and I’m sure Midiki will be the focus of a blog post or two in the future.

Kairui: ~5,620 speakers in suco Cairui, Manatuto

Naueti: ~20,830 speakers in eastern Viqueque

Atauran: ~9,810 speakers on Ataúro Island, just off the coast of the capital Dili

The varieties of Atauran are all closely related Wetarese, the language of the nearby Indonesian island of Wetar. One variety, Dadu’a, is also spoken on mainland Timor in on the coast of Manatuto. From what I know, these varieties are mutually intelligible with each other and with Wetarese.

This is by no means a full list of the Austronesian languages spoken in Timor-Leste, but for the sake of brevity, I will stop here and move on to the second group of languages in Timor-Leste: the non-Austronesian languages. If you are wishing for a truly comprehensive overview of East Timor’s languages, Geoffrey Hull, former director of research for the Timorese Instituto Nacional de Linguística, wrote a great one.

The Papuan Languages of Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste is home to four Papuan (i.e., non-Austronesian) languages: Makasae (the most spoken Papuan language outside of the island of New Guinea), Fataluku, Makalero, and Bunak. Together, these languages form a wider cluster of Papuan languages on Timor and nearby islands categorized by linguists as the Timor-Alor-Pantar family.

Although the Papuan languages of Alor and Pantar islands are much more numerous, the four languages spoken in Timor-Leste account for the vast majority of speakers of Timor-Alor-Pantar languages (Schapper 2020:6).

Makasae: ~155,700 speakers in Baucau, Lautém, and Viqueque

Fataluku: ~51,160 speakers in Lautém

Makalero: ~9,760 speakers in Ilimoar, Lautém

Bunak: ~107,500 speakers stradling the Timor-Leste-Indonesia border.

“We know very little about the full extent of dialect variation in the TAP [Timor-Alor-Pantar] languages spoken there and the widespread acceptance and adoption of language names may obscure diversity. For instance, there appear to be several intermediate language varieties between Makasae and Makalero.” (Schapper 2020:6)

I hope that this post didn’t come across as too long-winded. I’m very excited and invested in the topic of languages and linguistics in Timor-Leste, my home for the next two years. I’ll always appreciate questions, comments, and feedback on this post. What do you have questions about? What do you want to know?

Obrigadu,

Andy

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this newsletter are my own and in no way represent the views of the Peace Corps nor the U.S. Government.

References

Chen, Yen-ling. 2015. Tetun Dili and Creoles: Another Look. University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Department of Linguistics. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/73258. (10 August, 2023).

Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2023. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-sixth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.

Fischer, J. Patrick. 2012. This file was derived from: Sprachen Osttimors.png: - Source: East Timor Statistics Office. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sprachen_Osttimors-en.png. (9 August, 2023).

Hull, Geoffrey. 2004. The Languages of East Timor: Some Basic Facts. Instituto Nacional de Linguística: Universidade Nacional Timor Lorosa'e. https://web.archive.org/web/20080720024316/http://www.asianlang.mq.edu.au/INL/langs.html

Schapper, Antoinette. 2020. Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume 3. In The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar: Volume 3, vol. 3, 1–43. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501511158.

Taylor-Leech, Kerry Jane. 2012. Language choice as an index of identity: linguistic landscape in Dili, Timor-Leste. International Journal of Multilingualism. Routledge 9(1). 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.583654.

Williams-van Klinken, Catharina, and Rob Williams. 2015. Mapping the mother tongue in Timor-Leste Who spoke what where in 2010?

Papuan languages are not genetically categorized or grouped, and instead represent a loose areal categorization. The Trans-New Guinea family is probably the most well-accepted proposed familial grouping of ‘Papuan’ languages.

As a fellow linguist, I really appreciate your dive into East Timorese languages. It’s quite amazing how anyone anywhere can communicate.

Very fun read, even for those of us without a linguistics background. So, are most people you encounter in your community bilingual at minimum? Are there generational differences in language use? Situational differences in use? Market vs home vs school vs workplace, for ex? Thanks!